articles / New Music

Gay Guerilla: Julius Eastman Comes to Los Angeles

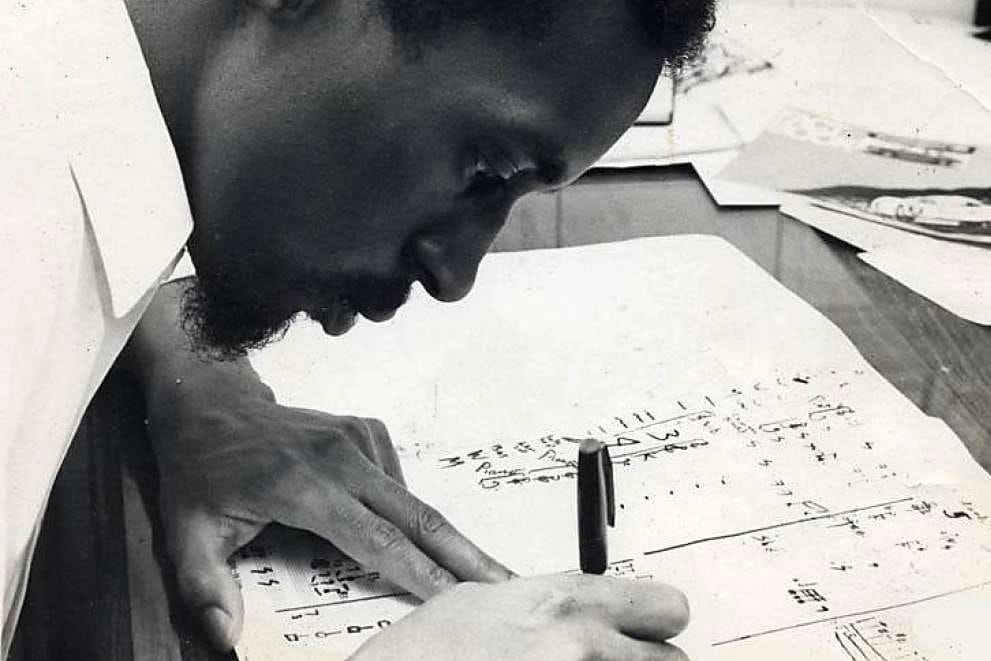

Composer Julius Eastman | Photo by Donald Burkhardt

Composer Julius Eastman | Photo by Donald Burkhardt

About Open Ears: So many people who made invaluable contributions to classical music were underappreciated in their time, or have been nearly lost to history. That’s why KUSC is starting Open Ears, a series of stories about composers, musicians, and conductors who deserve more recognition. You can learn more and explore other articles here.

Nearly 30 years after his death, music by composer Julius Eastman began popping up on programs around Los Angeles—his work, reflecting his conflicted experience as a gay Black American, finding new relevance among audiences.

“Talent is so precious, and he had such an original voice that I think he shouldn’t be buried, unknown. What Julius did that other composers may not have done,” says author Renée Levine-Packer, co-editor of Gay Guerilla: Julius Eastman and His Music, “was fuse jazz, even popular motifs or innuendos into classical. He liked choreographic aspects, he would bring people on and off the stage, and always included improvisation. That was different from the much more specific and mapped-out music by people like Steve Reich or Philip Glass.”

Eastman was born in 1940 in Manhattan and raised in Ithaca, New York—his mother had studied piano, and his father was the first Black graduate of the engineering school at NYU. Eastman showed a talent for music early on and a teacher suggested he audition for Juilliard. He didn’t get in there but was accepted to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia.

“There he became a true student of music, first studying piano and later changing to composition,” says Levine-Packer.

After graduation, Eastman went to Buffalo to sing in 1968. While he was there, he showed some of his compositions to Lukas Foss, conductor of the Buffalo Philharmonic and founder of the Center of the Creative and Performing Arts at SUNY Buffalo.

Foss invited Eastman to perform his compositions at a series inspired by Los Angeles’ Monday Evening Concerts. Eastman was named a new music fellow at the Center, and Levine-Packer, who was working at the Center, got to know him there.

“He sang, he played piano, he conducted, he did mime, he did everything,” she says. “Being close to Buffalo was also very important in the early ‘70s because of the Attica Prison uprising—Buffalo is very close to Attica. Before that he was calling his pieces The Moon’s Silent Modulation or Piano Pieces 1-4, but after Attica he started naming his pieces Gay Guerilla and Evil Nigger—these things were politically aggressive on purpose, he wanted to use very toxic words to be emphatic about what was going on and how he felt about it. He wanted us to confront these terribly difficult terms.”

Levine-Packer says the question of identity was a difficult one for Eastman.

“I think it was an on-going struggle in his life. He was Black and gay at a time when it was difficult to be either, let alone both. He found himself working in what was essentially a white precinct, there were hardly any Black people in classical music. His brother, Jerry Eastman, is a jazz musician who performed with Count Basie, and I think created a little irritation there about why Julius was so engaged in this classical world.”

Levine-Packer describes Buffalo as a bubble where it didn’t matter what color your skin was, or who you slept with, but after six years there—and much success—Eastman decided he needed to move on.

“He had an assistant professorship and he just walked away and went to New York, where he thought he had a good chance to make a mark. It proved more difficult than he suspected and there was a downward spiral. He started to act erratically, and people began to stay away.”

Eastman died at age 49 of cardiac arrest.

Unfortunately, much of his music was lost, but a trove of recordings was found in Buffalo and became the foundation for a 3CD set called Unjust Malaise that came out in 2005.